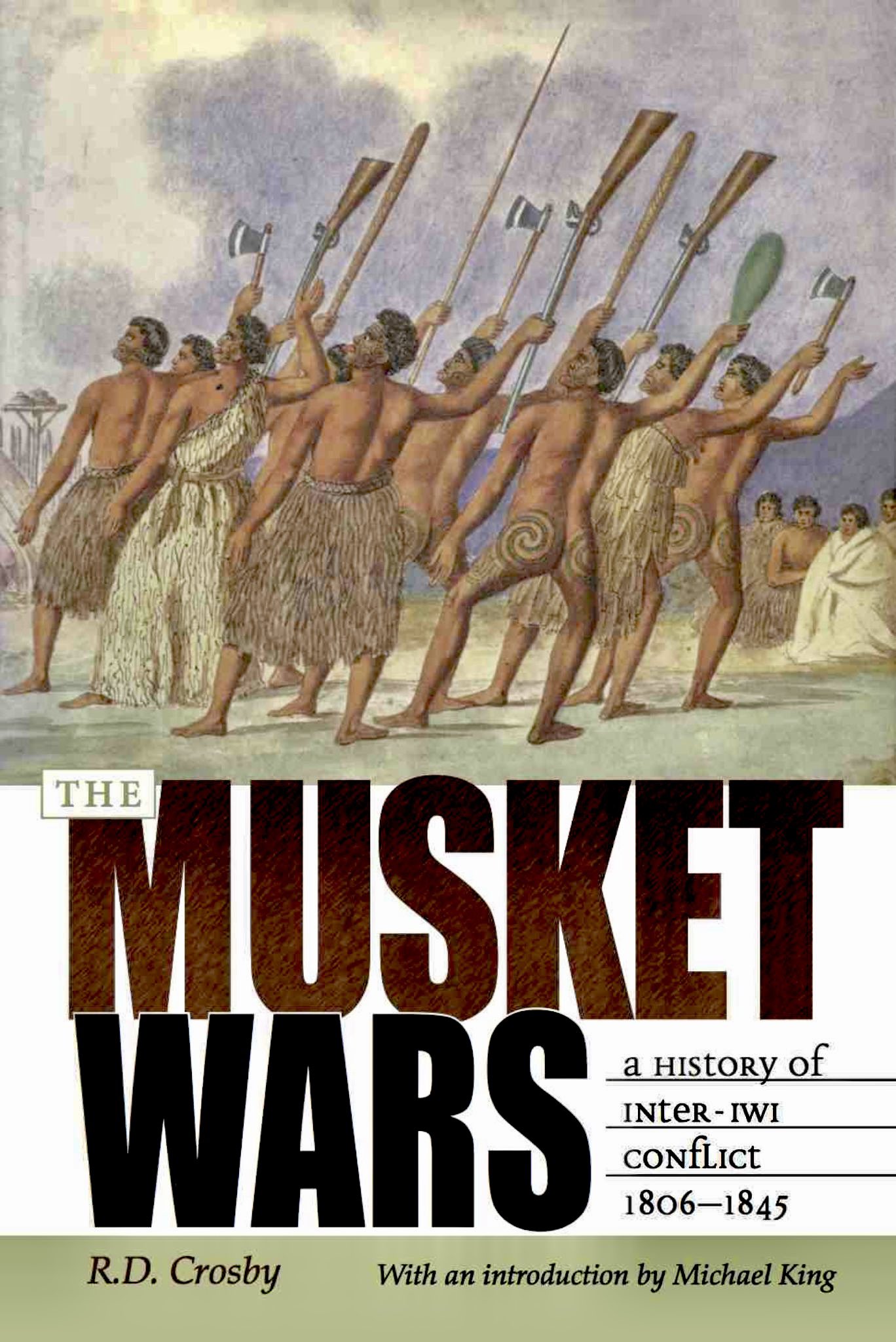

“In contrast to the pre-(European) contact days, when casualties might be measured in dozens and there were always survivors among the vanquished, now those same casualties might number hundreds, or, in a few dramatic instances, thousands.” In a nutshell, the introduction of muskets by Europeans led to an imbalance of power in 19th Century New Zealand: the Maori’s hand-held weapons were no match for the gun’s ability to kill quickly, from a long distance and at inflicting a far higher number of killed and wounded. Iwi (tribes) in Te Tai Tokerau (Northland) were the first to get their hands on the new weapons and conduct wide-sweeping taua (raids), which eventually led to iwi across the nation desperately trading flax and other resources in order to upgrade their ammunition. The resulting warfare claimed tens of thousands of lives, estimates vary between 20–60,000, killing, wounding or displacing up to half the Maori population as refugees; it exceeded the casualty figures of the later New Zealand Wars; it disrupted mana, land ownership and resources. The Musket Wars also had far-reaching consequences: desirable tracts of land that had been vacated because of the wars became the first locations to be purchased by the New Zealand Company and occupied by the early British settlers. The Musket Wars took place between 1807-1845 resulting in the most turbulent period of war in New Zealand’s history. These weapons were introduced by whalers and sealers, missionaries and timber traders and traders in flax. The first iwi to acquire muskets were those in Northland, predominately the Ngapuhi. Between 1818 and 1825 they and their cohorts swept aside the top half of the North Island. Much of the surface mythology soon gets swiftly dispatched and moves on to chronicle the stories of slaughter and slavery from the many warring tribes. Tales of women and children being tied to the back of waka (large scale war canoes) until drowned, as well as stories of children being murdered then eaten in front of their parents, none of this makes for easy reading. The sheer extent of savagery, torture and cruelty that Maori of one tribe inflicted on another, along with the sadism of occasional grave and corpse desecration to take the humiliation of vanquished enemies to the maximum is a full-on exposé of the fact that Maori never were an innocent race. No race ever has been. During the Musket Wars they continued to make slaves of the conquered in the tens of thousands. Identity political Marxist Maori today, the par-Maori descendants of these islands first Polynesian colonisers, base their never-ending grievance politics on the premise it is Critical Social Justice to hold alleged race-based hate crimes of the civilising British 200 years ago against the white New Zealanders of today, who include, but are not exclusively the descendants of the British. Given this is their standard viewpoint, it is reasonable that the par-Maori of today should also be held accountable for their ancestors’ many crimes against humanity, including slavery. It was part of Maori culture, no less despicable than most other cultures. And of course the reasonable moral standard to hold historical figures to is the best moral standard available to them in their time. Not contemporary standards. The details of the many atrocities that occurred during the Musket wars is very confronting stuff and reveals that the fiercely tribal Maori of pre first European contact times were a warlike people most definitely far more relentlessly violent, inhumane and unforgiving to each other, their feudalistic vendetta based justice and bloodthirsty cannibal feasts was far more brutal than anything the British newcomers of the 1800s ever inflicted on them. But the true significance of the Musket Wars goes well beyond the terrible inhumanities, death and destruction they caused. By the time the treaty was signed in 1840, Maori society had been turned on its head; […]